|

|

| My Daily Battle |

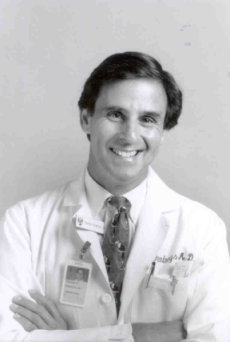

Dr. Thomas Graboys was a member of the cardiologist "dream team" that advised the late Celtics star Reggie Lewis. Four years ago, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and, later, an Alzheimer's-like dementia. Now 62 and living in Chestnut Hill, he shares what it's like to be trapped in your own body and betrayed by your own mind.

By Thomas Graboys | March 23, 2008

The daily struggle with Parkinson's disease is relentless. There is no reprieve, and the future is uncertain. Even on the good days, Parkinson's lurks like an unwanted shadow. In my case, Parkinson's is a 24-hour-a-day affair, because the associated Lewy body disease brings forth vivid nightmares and violent sleep on a weekly basis, nightmares so realistic that I am likely to act them out. I have dreamed of being attacked and, in an effort to fight back, have inadvertently struck my wife, Vicki.

In the mornings when I wake, or when I stir from the midday nap that has become as essential to functioning as my medication, I lie entombed in my own body for 10 to 15 minutes. This paralysis of mind and body lasts until enough synapses can muster themselves into action to allow me to move.

Neurological disarray affects every aspect of my life. Objects sometimes appear strangely flat and without dimension. Double vision is a problem. Minor hallucinations make it hard to trust my own eyes from time to time. I sometimes get disoriented and find myself lost momentarily in the house.

The common perception of Parkinson's as little more than body tremors is way off the mark. In many cases, like mine, the symptoms are global. No major function of mind or body has been spared. From visual perception, cognition, and speech to blood pressure, body temperature control, and sexuality, Parkinson's permeates every aspect of my being.

The once simple task of putting my arm through a sleeve can be exasperating. I often feel too hot and too cold simultaneously. Sudden drops in blood pressure bring me to the brink of fainting. I avoid some foods I once enjoyed because I can no longer manipulate my silverware well enough to cut a steak.

Physical deficits are only one part of my daily battle. My interactions with people are marked by a slowness of thought (called bradykinesia) that is as embarrassing as it is frustrating. It's more than losing my train of thought, though that happens a hundred times a day or more. It's having the words in my head, but being unable to move them from the part of the brain where thoughts are formed to the part that controls speech. The neural pathways are disorganized, like some fantastically complex highway system with overpasses and intersections, exit ramps and onramps, all leading nowhere.

It is this dementia, this progressive loss of cognitive and intellectual functioning, that is the hardest symptom of my disease to live with and the hardest to accept. I can no longer balance a checkbook or calculate a restaurant tip. The concentration required for two hours of often halting conversation leaves me weary. A veil descends, like a night canopy over a bird cage, and I need to nap to recharge my diminished synapses.

Initially, my social confidence was destroyed, and I resisted social occasions for a long time. But Vicki has rescued me from life as a recluse. She has always had an active social life with a wide circle of friends, and there are countless charitable functions on her calendar that force me to engage with the world.

We were invited to a buffet dinner on Wellesley College's magnificent campus. It was so crowded that you could hardly move and so noisy you could barely hear. My anxiety always spikes at such times. Sensory overload makes it harder to mask the symptoms of Parkinson's. The pressure to "perform" feels onerous and quickly becomes counterproductive. I couldn't muster the motor coordination to move food from the buffet table to my plate, and conversation, for several reasons, was impossible. The verbal sparring, the quick give-and-take that is so much a part of daily life, no longer takes place on a level playing field. For one thing, Parkinson's interferes with voice modulation, and I often speak, involuntarily, in a near whisper. The playing field is also tilted, because I am keenly aware that I am often well off the pace of the palaver. I often drop fancy words like "palaver" into my conversation to prove I still have "it," that I am not an intellectual shipwreck. Words I once thought pretentious I now use deliberately in conversation to compensate for the loss of intellectual firepower.

When we return home from these occasions, I am always eager for a debriefing from Vicki. "How was I?" I want to know. Often Vicki doesn't need to say anything. I know just from looking at her how the evening has gone.

Every day, something happens - some event large or small - that triggers my anger at what has happened to me. The anger, too, is pervasive. I am angry over my losses, angry about the terrible pain and anxiety my illness has introduced into the lives of my wife and daughters, angry at the loss of much of my sexuality, angry that my young grandchildren will never know "Pops" without dementia, angry that it takes me 20 minutes to change a light bulb, angry that the disease has ripped apart the fabric of my life, and angry at being dependent.

Despite the myriad symptoms and problems, I am optimistic that I can keep my situation stable. I believe this because I have to believe it. I have to believe that tomorrow can be as good as today. That is the most that I hope for.

Send comments to magazine@globe.com. Reprinted with permission of Sterling Publishing Co., from Life in the Balance by Thomas Graboys with Peter Zheutlin.

Copyright © 2007 by Thomas Graboys and Peter Zheutlin.

|